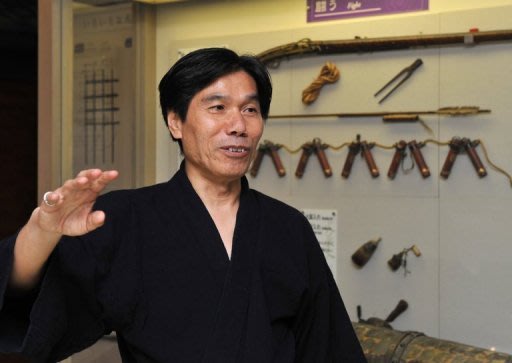

Photo By Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP

By Miwa Suzuki

(AFP) A 63-year-old former engineer may not fit the typical image of a dark-clad assassin with deadly weapons who can disappear into a cloud of smoke. But Jinichi Kawakami is reputedly Japan's last ninja.

As the 21st head of the Ban clan, a line of ninjas that can trace its history back some 500 years, Kawakami is considered by some to be the last living guardian of Japan's secret spies.

"I think I'm called (the last ninja) as there is probably no other person who learned all the skills that were directly" handed down from ninja masters over the last five centuries, he said.

"Ninjas proper no longer exist," he said as he demonstrated the tools and techniques used in espionage and sabotage by men fighting for their samurai lords in the feudal Japan of yesteryear.

Nowadays they are confined to fiction or used to promote Iga, some 350 kilometres (220 miles) southwest of Tokyo, a mountain-shrouded city near the ancient imperial capital of Kyoto that was once home to many ninjas.

Kawakami, a former engineer who began teaching ninjutsu -- the art of the ninja -- ten years ago, said the true history of ninjas was a mystery.

"There are some drawings of their tools but we don't always find all the details," which may have been left deliberately vague, Kawakami said.

"Many of their traditions were passed on by word of mouth, so we don't know what was altered in the process."

And those skills that have arrived in the 21st century in their entirety are sometimes difficult to verify.

"We can't try out murder or poisons. Even if we can follow the instructions to make a poison, we can't try it out," he said.

Kawakami first encountered the secretive world of ninjas at the age of just six, but has only vague memories of first meeting his master, Masazo Ishida, a man who dressed as a Buddhist monk.

"I kept practising without knowing what I was actually doing. It was much later that I realised I was practising ninjutsu."

Kawakami said training ranged from physical and mental skills to studies of chemicals, weather and psychology.

"I call ninjutsu comprehensive survival techniques," though it originated in war skills such as espionage and guerrilla attacks, he said.

"For concentration, I looked at the wick of a candle until I got the feeling that I was actually inside it. I also practised hearing the sound of a needle dropping on the floor," he said.

He climbed walls, jumped from heights and learned how to mix chemicals to cause explosions and smoke.

"I was also required to endure heat and cold as well as pain and hunger. The training was all tough and painful. It wasn't fun but I didn't think much why I was doing it. Training was made to be part of my life."

Kawakami said he was "a strange boy" growing up but his practice drew little attention at a time when many in Japan were struggling to make ends meet in the hard post-war years.

Just before he turned 19, he inherited the master's title, along with secret scrolls and special tools.

Kawakami is careful not to claim the title of the "last ninja" for himself and in the sometimes sectarian world of ninjutsu there are doubters and rival claimants, with the disputes centring on the authenticity of various teachings.

Kawakami says much of the ninja's art lies in catching people unawares, rather than in brute force.

"Humans can't be on the alert all the time. There is always a moment when they are off guard and you catch it," he said.

It is all about exploiting weaknesses that allows the ninja to outfox much bigger or more numerous opponents; distracting attention to allow a quick getaway.

It is possible to hide -- in a manner of speaking -- behind the smallest of things, Kawakami said.

"If you throw a toothpick, people will look that way, giving you the chance to flee.

"We also have a saying that it is possible to escape death by perching on your enemy's eyelashes; it means you are so close that he cannot see you."

Kawakami recently began a research job at the state-run Mie University, where he is studying the history of ninjas.

But, he said as he showed an AFP team around the Iga-ryu Ninja Museum and its trick house with hidden ladders, fake doors and an underfloor sword box, he is resigned to the fact that he is the last of his kind.

There will be no 22nd head of the Ban clan because Kawakami has decided not to take on any more apprentices.

"Ninjas just don't fit in the modern day," he said.

Link:

No comments:

Post a Comment