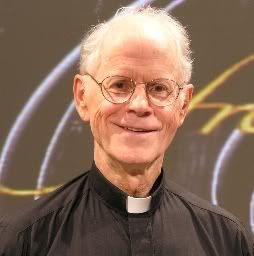

By

Cardinal George Pell

FAR from bringing equality, contraception has redistributed power away from women, says George Pell.

The Australian - THIS year is the 50th anniversary of the contraceptive pill, a development that has changed Western life enormously, in some ways most people do not understand.

While majority opinion regards the pill as a significant social benefit for giving women greater control of their fertility, the consensus is not overwhelming, especially among women.

A May CBS News poll of 591 adult Americans found that 59 per cent of men and 54 per cent of women believed the pill had made women's lives better.

In an article in the ecumenical journal First Things that month, North American economist Timothy Reichert approached the topic with "straight-forward microeconomic reasoning", concluding that contraception had triggered a redistribution of wealth and power from women and children to men.

Applying the insights of the market, he points out that relative scarcity or abundance affects behaviour in important ways and that significant technological changes, such as the pill, have broad social effects. His basic thesis is that the pill has divided what was once a single mating market into two markets.

This first is a market for sexual relationships, which most young men and women frequent early in their adult life. The second is a market for marital or partnership relationships, where most participate later on.

Because the pill means that participation in the sex market need not result in pregnancy, the costs of having premarital and extra-marital sex have been lowered.

The old single mating market was populated by roughly the same number of men and women, but this is no longer the case in the two new markets.

Because most women want to have children, they enter the marriage market earlier than men, often by their early 30s. Men are under no such constraints.

Evolutionary biology dictates that there will always be more men than women in the sex market. Their natural roles are different. Women take nine months to make a baby, while it takes a man 10 minutes. St Augustine claimed that the sacrament of marriage was developed to constrain men to take an interest in their children.

Men leave the sex market at a higher average age than women to enter the marriage market.

This means that women have a higher bargaining power in the sex market while they remain there (because of the larger number of men there) but face much stiffer competition for marriageable men (because of the lower supply) than earlier generations.

In other words, men take more of "the gains from trade" that marriage produces today.

Reichert also claims that this market division produces several self-reinforcing consequences, including more infidelity.

From a Christian viewpoint it is incongruous and inappropriate to consider baby-free infidelity as an advantage for women or men.

But younger women are likelier to link up with older, successful men than older women with young men, as any number of married women can attest after rearing children, only to find their husband has left for a younger woman.

Another consequence is a greater likelihood of divorce. Because of their lower bargaining power, more women strike "bad deals" in marriage and later feel compelled to escape. This is easier today because the social stigma of divorce has declined and because of no-fault divorce laws.

More women also can afford to divorce and, in some cases, prenuptial agreements provide insurance against the worst.

Only the official teaching of the Catholic Church remains opposed to the pill and indeed all artificial contraception, but this is not even a majority position among Catholic churchgoers of child-bearing age.

Indeed, this particular Catholic teaching is often cited as diminishing the church's authority to teach on morality among Catholics themselves, as well as provoking disbelief and even astonishment among other Christians and non-believers.

Catholic teaching does not require women to do nothing but have children but it does ask couples to be open to kids and to be generous.

What this means in any particular situation is for each couple to decide.

Progressive Catholic opinion 40 or 50 years ago urged believers to follow their consciences and reject the church's opposition to artificial contraception. Today's advocates of the primacy of personal conscience urge Catholics to pick and choose among the church's teachings on marriage, sexuality and life issues, although they generally allow fewer liberties in social justice or ecology.

These changes, regarded as progressive or misguided depending on one's viewpoint, are not coincidental but follow from the revolutionary consequences of the pill on moral thinking and social behaviour; on the broadening endorsement of a moral individualism that ignores or rejects as inevitable the damage inflicted on the social fabric. This revolution was reinforced by the music of the 1960s, for example Mick Jagger's Rolling Stones, or the Beatles.

While early Catholic supporters of the pill claimed it would diminish the number of abortions, this has not eventuated. Whatever the causes, abortion rates have increased dramatically since the mid-60s in Australia and the US, although the number has peaked.

Real-life experience suggests that the "contraceptive mentality" pope Paul VI warned about in 1968 has had unforeseen consequences. To paraphrase Reichert, an unwanted baby threatens prosperity and lifestyle, making abortion seem necessary.

It is the women who bear most of the burden of trauma and grief from abortions.

Even women who believe deeply in the Christian notion of godly forgiveness, and those who do not believe in God at all, can battle for years with unassuaged guilt.

In support of his claims that women are bearing a disproportionate burden in the new paradigm, Reichert cites evidence that in the past 35 years across the industrialised world women's happiness has declined absolutely and relative to men.

We have a new gender gap where men report a higher subjective wellbeing. This decline in women's happiness coincides broadly with the arrival of the sexual revolution, triggered by the invention of the pill.

The ancient Christian consensus, which lasted for 1900 years, linking sexual activity to the lovemaking of a husband and wife to create new life, was first broken by the Anglican Church's Lambeth Conference approval of contraception in 1930.

In this new contraceptive era, where no Western country produces enough children to maintain population levels, the Catholic stance is isolated, rejected and often despised.

But the use of the contraceptive pill not only changes the dynamics within a family between husband and wife, it is also changing our broader society in ways we understand imperfectly.

But 50 years is not a long time; it is still early in the story.

Cardinal George Pell is the Catholic Archbishop of Sydney.

"Impressionable

"Impressionable

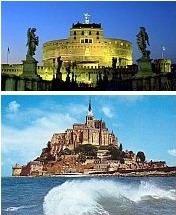

formerly Hadrian's tomb, but which was converted to papal use, connected to the Vatican by a long tunnel. A statue of St. Michael sits atop the building today (picture at top right).

formerly Hadrian's tomb, but which was converted to papal use, connected to the Vatican by a long tunnel. A statue of St. Michael sits atop the building today (picture at top right).

The Michaelmas Daisies, among dede weeds,

The Michaelmas Daisies, among dede weeds,

than give up their faith. What is amazing is the number of witnesses to these executions who became converted. The Christians even converted many of their guards to the Catholic Faith and in turn, many of these became martyrs. How many of us would become Catholic if we knew that we would be executed and had witnessed others being executed?

than give up their faith. What is amazing is the number of witnesses to these executions who became converted. The Christians even converted many of their guards to the Catholic Faith and in turn, many of these became martyrs. How many of us would become Catholic if we knew that we would be executed and had witnessed others being executed?

![[Family+Praying+The+Rosary.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjpyjCYJOPKs_TiuI9h94VzvKMpx2pfGpyyg7Pf7i-3XWmoBltYMCoPO9lQOBjSWlMFc49RKsnLInsyZlC2M8YMaZEo-KHS7jaSHiaCaoDQCIsZgVNxjXSgyGjH-il8FnnkRia9En4K20Q/s1600/Family+Praying+The+Rosary.jpg)